Why You Shouldn’t Swing Down on the Ball...a deep(ish) dive.

- msilver851

- Sep 1, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 2, 2025

Why You Shouldn’t Swing Down on the Ball

For decades, hitters were told to “swing down on the ball” to create backspin and lift. But modern analysis shows this cue often hurts more than it helps, and it runs counter to how elite hitters, including Ted Williams, actually swung.

Disclaimer: This reflects only the opinion of the Red Wings Performance Center team. Before making any adjustments to your swing, we recommend consulting with your own hitting coach or trusted guru to ensure these ideas make sense to your game.

TL;DR

Swinging down on the ball is an outdated cue. While actually swinging down on the ball may create additional backspin, it costs you valuable exit velocity and leads to weak ground balls. Data shows batted balls hit 95+ mph with positive launch angles produce far higher batting averages and slugging percentages than weak contact. Ted Williams himself preached swinging up into the ball to match the pitch plane, giving hitters a larger margin for error and more consistent hard contact. The modern approach: train to match the plane, hit flush, and focus on exit velocity and launch angle, not chopping down.

What the Data and Physics Reveal

Swinging down does generate more backspin...but the minimal carry you gain is far outweighed by the exit velocity you lose by chopping down on the ball.

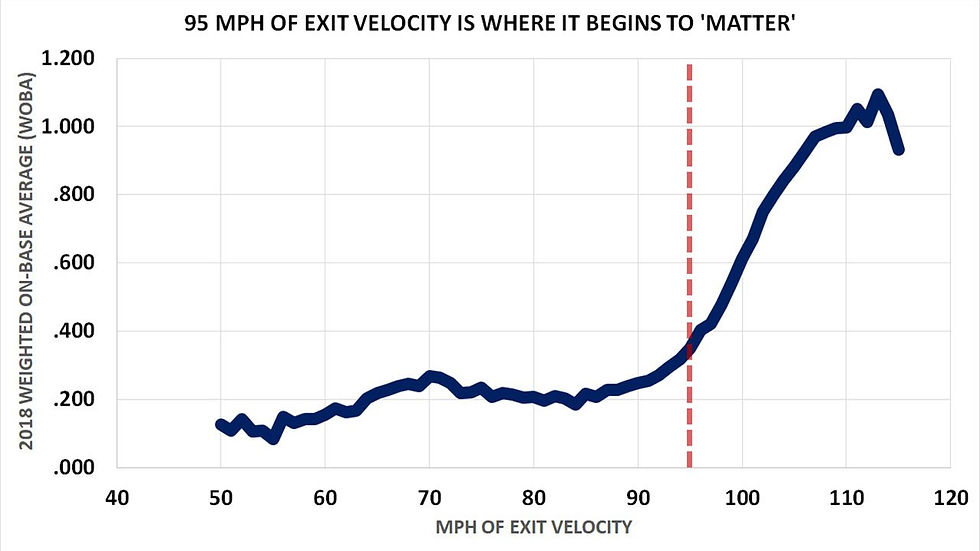

Higher exit velocity + positive launch angle = better outcomes. Batted balls with EV over 95 mph yield much stronger results... in one study, these “hard-hit” balls produced a .524 batting average and .653 wOBA, versus a .219 BA and .206 wOBA on weaker hits .

Matching the pitch plane increases contact consistency and energy transfer. Driveline Baseball notes that aligning the bat’s attack angle with the pitch reduces energy loss at contact and expands your margin for error .

A biomechanical study confirms that how the bat approaches the ball (the “undercut angle”) strongly affects both launch angle and exit velocity...showing that a proper upward or level path surpasses chopping down.

What Ted Williams Taught Us

Ted Williams, one of the greatest hitters ever, emphasized swinging up into the ball, not down on it. In The Science of Hitting, he advocated for aligning the swing plane with the incoming pitch—around +5° for fastballs, 10–15° for breaking balls—to maximize contact and carry.

TL;DR: Why a Downward Swing Holds You Back

Myth | Reality |

“Swinging down creates backspin and the ball goes further.” | True, but the EV you lose from chopping far outweighs any marginal carry you *may* gain (ballooning effect). |

“I’ll hit more grounders, but at least it’s safe.” | Grounders are the lowest slugging category; hard lofted contact is far more valuable. |

“Swinging down helps me get on top of the ball.” | The best hitters match the pitch’s plane or swing up, increasing both consistency and power. |

What to Do Instead

Match the pitch plane – Train a slight upward path (~5°) into the ball, especially for fastballs.

Focus on flush contact – Hard contact at proper launch angles translates into consistent success.

Use modern drills – Tools like weighted (hitting) plyos or bat sensors, like Blast Motion, help reinforce swing paths that are “on plane,” not downhill.

MLB Statcast bat-tracking check (what “on-plane” really looks like)...

Attack Angle (AA) is the vertical direction of the bat at impact; 5–20° is the “ideal” window, per MLB Statcast’s bat-tracking glossary. League-wide, the average AA is ~10°...slightly up into the ball, not down.

Snapshot example (2025 leaderboard via Baseball Savant):

James Wood: ~11° AA (with a steeper swing-path tilt) - squarely in the “ideal” band.

Vladimir Guerrero Jr.: ~2° AA (flatter) - still positive, and paired with elite bat speed.

Different hitters, different shapes, but both positive attack angles, reinforcing that scalable contact comes from meeting the pitch on an upward path, not chopping down.

Statcast also flags that contacting the ball with 5-20° AA is “ideal”, and defines hard-hit as 95+ mph EV, the threshold where damage really spikes. Use EV + AA to confirm your approach is putting you in position for repeatable impact, not just lucky outcomes.

➡️ Check out your favorite player using Baseball Savant’s bat-tracking visuals...you can see their swing path, attack angle, and contact profile in interactive form.

The Real vs. Feel Argument

A lot of hitting cues come from feel. Coaches might tell a player to “swing down” because it feels like that helps them get on top of the ball or stay short to it. Sometimes, introducing that cue in practice can even correct another flaw in your move...like an exaggerated uppercut or a long/early disconnected barrel path.

But here’s the catch: feel is not real. High-speed video and bat sensors show that elite hitters don’t actually chop down. Their barrels move on a slightly upward path into contact, matching the angle of the incoming pitch. That’s what produces flush, high-exit-velocity contact that consistently turns into extra-base hits.

So while “swing down” might be useful as a feel to counteract another bad habit, the reality is that your bat still needs to travel up into the ball. This is why we use objective feedback...exit velocity, launch angle, attack angle...to separate what feels right from what actually works.

How Pitch Location Impacts Attack Angle

Attack angle isn’t a fixed number...it shifts depending on where in the zone you’re attacking. On high pitches, hitters naturally adjust with a flatter attack angle to square the ball up, while on low pitches, the swing path has to tilt upward more steeply to stay on plane with the ball’s descent. That’s why elite hitters don’t live at just one attack angle...they operate within a range (5–20° is “ideal”) that adapts to location. The key is that across all zones, successful hitters still keep the barrel working up into the ball, not chopping down.

Statcast shows that hitters’ attack angles vary significantly depending on pitch location. On low pitches, the average Attack Angle (AA) spikes up to around 16°...a steeper upward path to stay on plane. On middle and high pitches, it drops to ~9° and 7°, respectively .

That means elite hitters are adjusting their swing plane based on pitch height, not staying at a fixed angle.

Example: Aaron Judge

His overall average AA is ~14°, in the upper ideal range (source: Batting title favorites Judge, Wilson couldn't be more different).

Against low pitches, he likely lifts the barrel more, helping him stay on plane and drive the ball.

Against high pitches, his AA naturally flattens—but it remains positive, helping ensure consistent contact.

Takeaway: Good hitters adapt. The goal isn’t a fixed swing plane, but meeting the ball on an upward path appropriate to pitch height. That adaptability equals better, more scalable contact across all zones.

There’s also more to this story: Timing and attack angle are deeply connected...and that’s part of why “swing down” can sometimes feel right. But the real key is syncing bat path and contact point to maximize the on-plane window…we’ll get into this in a later blog.

Bottom Line

Swinging down at the ball is a relic of outdated coaching. It sacrifices exit velocity, shortens margins for error, and doesn’t reflect how great hitters actually swing.

As the great Steve Springer once said... "We know too much, now."

Instead, align your bat with the pitch plane...just like Ted Williams taught...and hit the ball hard and square.

Who’s your favorite player to watch swing...and what makes their swing stand out to you? Comment below.

Acknowledgment

A special thanks to Driveline Baseball for openly sharing research on swing plane, attack angle, and exit velocity (among many other topics)...their willingness to publish findings has helped coaches and players across all levels. Likewise, credit to Mike Petriello and the MLB Advanced Media team for their work on Baseball Savant, which continues to provide the most accessible and user-friendly data tools available. Together, they’ve made advanced baseball research and tools available to the wider community.

Sources & Further Reading

Williams, Ted. The Science of Hitting. Simon & Schuster, 1971.

Sports Illustrated Vault. “A Real Rap Session.” SI Vault, April 14, 1986.

FanGraphs Blog. “The Lurking Influence of Batted-Ball Spin.” FanGraphs, July 2021.

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/the-lurking-influence-of-batted-ball-spin/

Neal, Bryce. “Objective Approach: Attack Angle Part 1.” Medium, Jan 29, 2020.

https://coachnealpt.medium.com/objective-approach-attack-angle-part-1-8daf25875f8a

Hitterish blog. “Ted Williams Swing — The Science of Hitting.” Aug 27, 2017.

https://www.hitterish.com/single-post/ted-williams-swing-analysis

The Boston Globe. “A Look at J.D. Martinez’s Swing, and the Secret to Launch Angle.” March 27, 2018.

https://apps.bostonglobe.com/sports/graphics/2018/01/launch-angle/

Driveline Baseball. “Using Swing Plane to Coach Hitters: a Deeper Look.” May 29, 2018.

https://www.drivelinebaseball.com/2018/05/using-swing-plane-coach-hitters-deeper-look/

MLB.com / Petriello, Mike. “4 New Swing Metrics Tell Us More Than We’ve Ever Known About Contact.” May 20, 2025.

https://www.mlb.com/news/new-swing-metrics-tell-us-more-about-contact

MLB.com / Adler, David. “Batting Title Favorites: Judge vs. Wilson.” June 27, 2025.

https://www.mlb.com/news/aaron-judge-vs-jacob-wilson-by-the-numbers

Comments